Pollinator Post 9/1/23 (2)

The Blister Galls are out of control on the California Goldenrod, Solidago velutina ssp. californica. The galls, as well as caterpillars have exacted a heavy toll on the plants along Skyline Trail. Many have simply withered away, and those that survived produce meager flowers.

The blisters are actually a well-known goldenrod gall, induced by the gall midge Asteromyia carbonifera (family Cecidomyiidae). The midge induces flat, circular galls in the leaves of various goldenrods (Solidago). One to ten or more larvae develop in each gall. Color and size of the gall vary by host species and number of larvae. The galls contain a symbiotic fungus, Botryosphaeria dothidea, which the larva apparently does not eat. The fungus seems to confer some protection against parasitoid wasps. Females carry spores of the fungus.

Close-up of a blister gall on a leaf of California Goldenrod. There seem to be tiny puncture holes in the raised portion. Have the gall flies emerged? Or has the gall been invaded by parasitoids? Since there are so many of these galled leaves, I decide to collect a few with mature galls to rear out the insects at home.

The Wood Ferns on the steep slopes along Skyline Trail provide great support for the three-dimensional webs of the Sheetweb Weavers (family Linyphiidae).

In the shade, droplets of fog festoon the orb web of a Conical Trashline Orbweaver, Cyclosa conica (family Araneidae).

Close-up of the Conical Trashline Orbweaver, Cyclosa conica resting head-down in the center of her crystal palace. She’s the palest specimen I have ever seen. Maybe newly molted?

Trashline spiders are so-called for their web decoration. Cyclosa create orb-shaped webs using both the sticky and non-sticky threads, mostly during times of complete darkness. Across its spiral wheel-shaped web, Cyclosa fashions a vertical “trashline” made of various components such as prey’s carcasses, detritus, and at times, egg cases. The trashline helps the spider to camouflage exceptionally well from predators. The spider sits in the web hub to conduct its sit-and-wait hunting, ensnaring prey at nearly any time of day; it only leaves its spot to replace the web prior to sunrise.

A tiny midge is running swiftly on the surface of a California Bay leaf. Of the dozen pictures I took, only this one has parts of the insect in focus. It appears to be a Fungus Gnat, family Mycetophilidae.

The Mycetophilidae are a family of small flies, often known by their common name of Fungus Gnats. They are generally found in the damp habitats favored by their host fungi and sometimes form dense swarms. The delicate-looking flies are similar in appearance to mosquitoes. Adults have slender legs, and segmented antennae that are longer than their head. Adult fungus gnats do not damage plants or bite people. Larvae, however, when present in larger numbers, can damage roots and stunt plant growth. Females lay tiny eggs in soil or moist organic debris. Most of the fungus gnat’s life is spent as a larva and pupa in organic matter or soil. There may be many overlapping generations each year. They are most common during winter and spring in California when water is more available and cooler temperatures prevail.

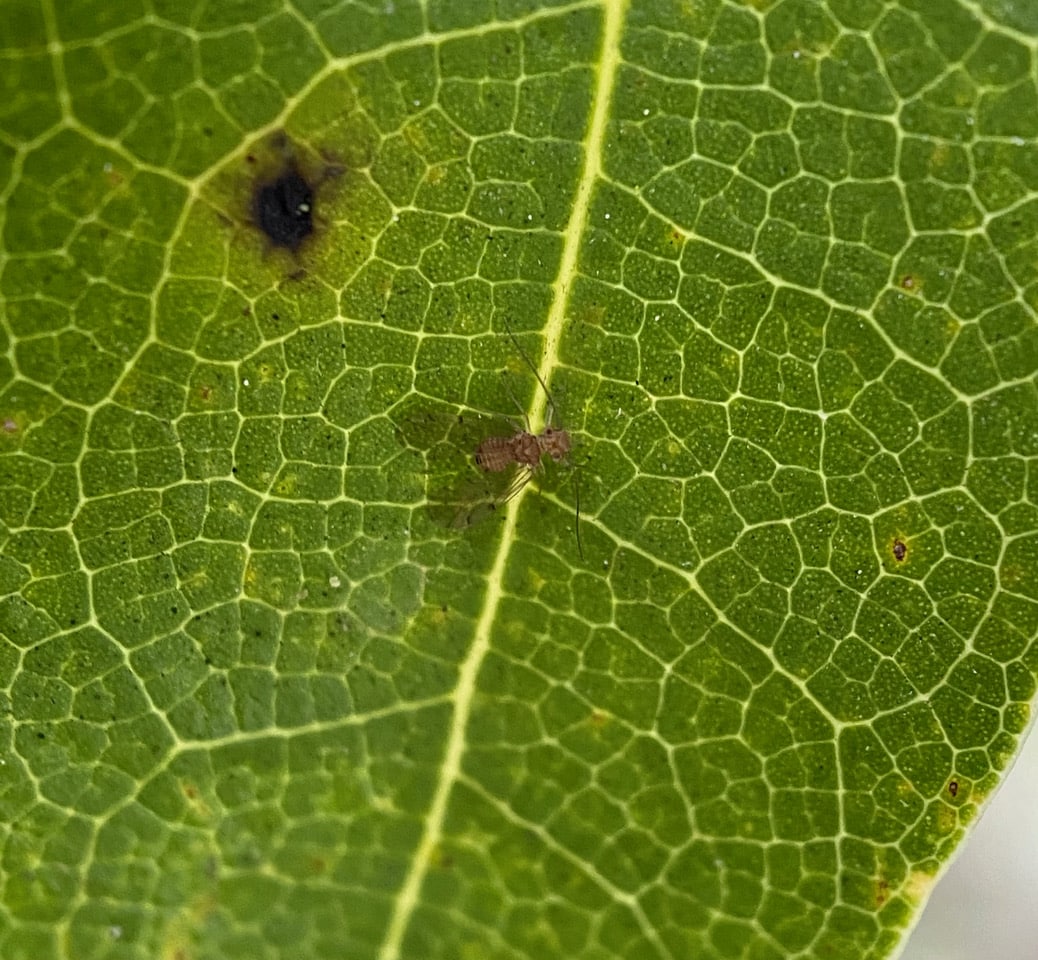

Even smaller than the midge is this odd looking insect, less than 2 mm. It is an Outer Barklouse in the family Ectopsocidae (order Psocodea, formerly Psocoptera).

The scientific name comes from the Greek psocus (to grind) and refers to the psocopteran jaws, which are shaped to grind food, rather like a pestle and mortar. These insects are conveniently discussed in two groups – barklice that live outdoors, and booklice that are found in human habitations.

Barklice are usually found in moist places, such as leaf litter, under stones, on vegetation or under tree bark. They have long antennae, broad heads and bulging eyes. They feed on algae, lichens, fungi and various plant matter, such as pollen. Barklice are usually less than 6 mm, and the adults are often winged. The wings are held roof-like over their bodies. Some species are gregarious, living in small colonies beneath a gossamer blanket spun with silk from labial glands in their mouth. Sometimes the colonies seem to move in coordinated fashion, rather like sheep.

Booklice are wingless and are much smaller (less than 2 mm). They are commonly found in human dwellings, feeding on stored grain, book bindings, wallpaper paste and other starchy products, and on the minute traces of mold found in old books.

Psocodea undergo incomplete metamorphosis. They are regarded as the most primitive amongst the hemipteroids (true bugs, the thrips and lice) because their mouthpart show the least modification from those of the earliest known fossils.

The family Ectopsocidae includes fewer than 200 species, most of them in the genus Ectopsocus. They are found to inhabit dead leaves on tree branches and leaf litter. They are brown, small-sized barklice, 1.5-2.5 mm in length. Forewings are short, broad, and held in horizontal position (rather than tent-like as in other psocids).

To complete the menagerie of miniatures found on the California Bay leaf today, here’s one of our smallest native ants, the Ergatogyne Trailing Ant, Monomorium ergatogyna (family Formicidae).

The Ergatogyne Trailing Ant, Monomorium ergatogyna (family Formicidae) is native to California, Nevada, and Utah and are usually found in cities or on the coast. The ant is a shiny black color and contains only a single worker caste, making them a monomorphic species. It is also polygyne, meaning a colony contains multiple fertile queens living together. The workers are only 1.5 – 2mm long. The ants are scavengers that consume anything from bird droppings, dead insects to aphid honeydew. Sadly, Argentine Ants have been discovered to be actively pushing this species out of its original territory.