Pollinator Post 7/29/25 (2)

The night-blooming flowers of Datura are fast fading in the morning heat. There doesn’t seem to be any bee activity on these giant moth-pollinated flowers today. But look, there’ a tiny insect near the tip of the long style.

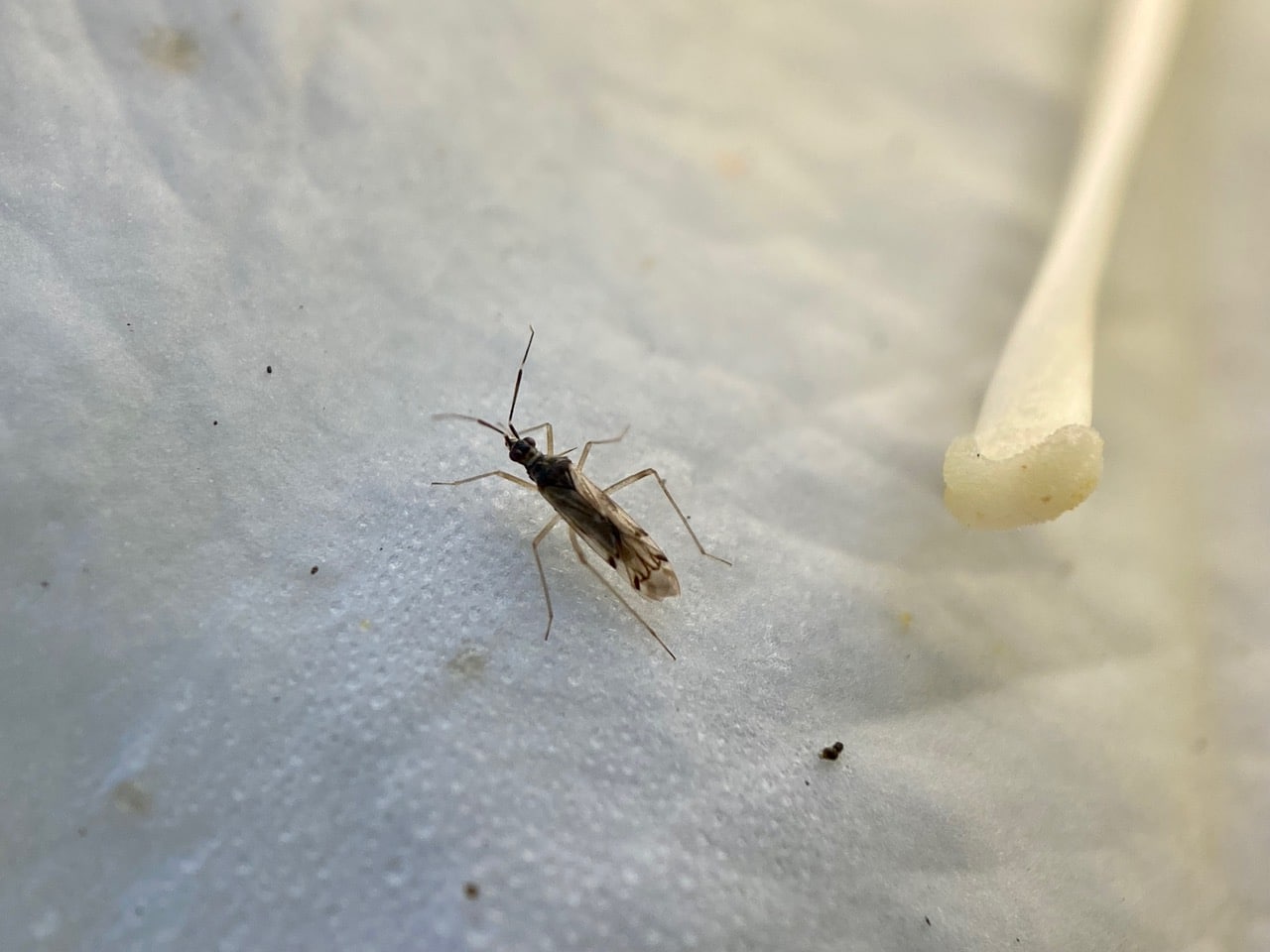

Under the macro lens, the tiny insect next to the Datura stigma turns out to be a Plant Bug. iNaturalist has helped identify it as a Tomato Bug, Engytatus modestus (family Miridae).

Mirid bugs are also referred to as plant bugs or leaf bugs. Miridae is one of the largest family of true bugs in the order Hemiptera. Like other Hemipterans, Mirids have piercing, sucking mouthparts to extract plant sap. Some species are predatory. One useful feature in identifying members of the family is the presence of a cuneus; it is the triangular tip of the corium, the firm, horny part of the forewing, the hemielytron. The cuneus is visible in nearly all Miridae.

The Tomato Bug, Egytatus modestus (family Miridae) is found in the Caribbean, Central America, North America, and South America. The adult is a slender bug, about 6mm long with long legs. It is noteworthy that Datura and tomato are in the same family (Solanaceae). Both adults and nymphs of the Tomato Bug feed on plants by inserting their piercing, sucking mouthparts into leaves and stems. Their feeding may cause leaves to shrivel and die. While the Tomato Bugs may damage tomato, they are facultative predators, meaning they can feed on both insects and plants. They are predaceous on small, soft-bodied insects such as whiteflies, aphids, and the eggs of various lepidopteran species and may provide a measure of biocontrol in some situations.

The California Yampah, Perideridia californica (family Apiaceae) is in peak bloom at the garden. The individual umbels of tiny flowers are quite inconspicuous, but they can be quite beautiful when massed together.

A Mason Wasp, Ancistrocerus bustamente (family Vespidae, subfamily Eumeninae) is taking nectar on an umbel of Yampah flowers.

Potter wasps (or mason wasps), the Eumeninae, are a cosmopolitan wasp group presently treated as a subfamily of Vespidae. Most eumenine species are black or brown, and commonly marked with strikingly contrasting patterns of yellow, white, orange, or red. Their wings are folded longitudinally at rest. Eumenine wasps are diverse in nest building. The Mason Wasps are species that generally nest in pre-existing cavities in wood, rock, or other substrate. Potter Wasps are the species that build free-standing nests out of mud, often with a spherical mud envelope. The most widely used building material is mud made of a mixture of soil and regurgitated water.

All known Eumenine species are predators, most of them solitary mass provisioners. When a cell is completed, the adult wasp typically collects beetle larvae, spiders, or caterpillars and, paralyzing them, places them in the cell to serve as food for a single wasp larva. As a normal rule, the adult wasp lays a single egg in the empty cell before provisioning it. The complete life cycle may last from a few weeks to more than a year from the egg until the adult emerges. Adult mason wasps feed on floral nectar.

The Mason Wasp, Ancistrocerus bustamente (family Vespidae, subfamily Eumeninae) is found in western North America and Mexico. The species frequents arid areas, and nests in pre-existing cavities (e.g. old borings in wood, hollow stems, rock crevices) and use mud for partitions between brood cells. The wasps have been known to nest in Sambucus (Elderberry) stems. The name of the genus means “hooked horn” for the back-curved last segments of the antennae characteristic of the males.

A tiny wasp is roaming the flowers Yampah (that appear huge in this magnification). For its size, I suspect that the wasp is a parasitoid. iNaturalist has helped identify it as a member of the subfamily Eucoilinae (family Figitidae).

Figitidae is a family of parasitoid wasps that has a worldwide distribution. Eucoilines have been reared from flies breeding in fruits, notably fruit flies in the families Tephritidae and Drosophilidae. Members of the subfamily Eucoilinae are solitary endoparasitoids that lay eggs in the larval stages of Cyclorrhaphous Diptera and emerge as adults from the host puparium. Some species have been used in biological control efforts against fruit flies.

Many Yellowjacket wasps are foraging on the Yampah flowers. I had hopes of finding the caterpillars of Anise Swallowtail butterflies on the Yampah, but seeing so many wasps, I am sure any caterpillars would have been preyed upon by now.

Yellowjacket is the common name for predatory social wasps of the genera Vespula and Dolicovespula (family Vespidae). Yellowjackets are social hunters living in colonies containing workers, queens, and males (drones). Colonies are annual with only inseminated queens overwintering. Queens emerge during the warm days of late spring or early summer, select a nest site, and build a small paper nest in which they lay eggs. They raise the first brood of workers single-handedly. Henceforth the workers take over caring for the larvae and queen, nest expansion, foraging for food, and colony defense. The queen remains in the nest, laying eggs. Later in the summer, males and queens are produced. They leave the parent colony to mate, after which the males quickly die, while fertilized queens seek protected places to overwinter. Parent colony workers dwindle, usually leaving the nest to die, as does the founding queen. In the spring, the cycle is repeated.

Yellowjackets have lance-like stingers with small barbs, and typically sting repeatedly. Their mouthparts are well-developed with strong mandibles for capturing and chewing insects, with probosces for sucking nectar, fruit, and other juices. Yellowjacket adults feed on foods rich in sugars and carbohydrates such as plant nectar and fruit. They also search for foods high in protein such as insects and fish. These are chewed and conditioned in preparation for larval consumption. The larvae secrete a sugary substance that is eaten by the adults.

The Western Yellowjackets typically build nests underground, often using abandoned rodent burrows. The nests are made from wood fiber that the wasps chew into a paper-like pulp. The nests are completely enclosed except for a small entrance at the bottom. The nests contain multiple, horizontal tiers of combs within. Larvae hang within the combs.

A Thick-legged Hover Fly, Syritta pipiens (family Syrphidae) is foraging on the Yampah flowers.

Syritta pipiens originates from Europe and is currently distributed across Eurasia and North America. They are fast and nimble fliers. The fly is about 6.5 – 9 mm long. The species flies at a very low height, rarely more than 1 m above the ground. Adults visit flowers – males primarily to feed on nectar, and females to feed on protein-rich pollen to produce eggs. The species is found wherever there are flowers. It is also anthropophilic, occurring in farmland, suburban gardens, and urban parks. Larvae are found in wetlands that are close to bodies of freshwater such as lakes, ponds, rivers, ditches. Larvae feed on decaying organic matter such as garden compost and manure. Males often track females in flight, ending with a sharp dart towards them after they have settled, aiming to attempt forced copulation.

Most of the flowers of the Showy Milkweed, Asclepias speciosa have faded, giving way to developing fruits with fuzzy skin.

Most of the seed pods of the Showy Milkweed are subtended by oddly curved peduncles. Why? To orient the seed pods to optimize eventual seed dispersal?

These two seed pods develop from the same cluster of Showy Milkweed flowers. The one to the left is already occupied by the yellow Oleander Aphids, Aphis nerii (family Aphididae).

Close-up of the Oleander Aphids, Aphis nerii (family Aphididae) feeding on the developing milkweed seed pod.

Aphis nerii is also known as Milkweed Aphid. The species is widespread in regions with tropical and Mediterranean climates. The species probably originated in the Mediterranean region, the origin of its principal host plant, oleander. This bright yellow aphid, measuring 1.5-2.6 mm, has black legs, antennae and cornicles (“tail pipes”). The aphids feed primarily on the sap of plants in the dogbane family, Apocynaceae, including Milkweeds, Oleander and Vinca.

Females are viviparous and parthenogenetic, meaning that they give birth to live young instead of laying eggs, and that the progeny are produced by the adult female without mating. The nymphs feed gregariously on the plant terminal in a colony that can become quite large. Nymphs progress through five nymphal instars without a pupal stage. Normally wingless adults are produced but alate adults occur under conditions of overcrowding and when plants are senescing, allowing the aphids to migrate to new host plants. The parthenogenetic mode of reproduction, high fecundity, and short generation time allow large colonies of Oleander Aphids to build quickly on infested plants.

The Oleander Aphid ingests sap from the phloem of its host plant. The damage caused by aphid colonies is mainly aesthetic due to the large amounts of sticky honeydew produced by the aphids and the resulting black sooty mold that grows on the honeydew. The terminal growths of host plants may be deformed, resulting in stunted growth in heavy infestation.

Oleander Aphids sequester cardiac glycosides, a toxin from their host plants. They also fortify their cornicle secretions with these bitter, poisonous chemicals. Their bright aposematic (warning) coloration and possession of toxins protect them from predation by certain species of birds and spiders. Aphid populations are usually kept under control by natural biological agents such as parasitoid wasps, and predators such as Syrphid larvae, Lacewing larvae, and Lady Beetles.

Look, behind the family of Oleander Aphids in the foreground is a stalked Lacewing egg. Mama Lacewing has wisely deposited her egg near the aphids to ensure that when the young hatches, it will have plenty to eat.

Lacewings are insects in the large family Chrysopidae of the order Neuroptera. Adults are crepuscular or nocturnal. They feed on pollen, nectar and honeydew supplemented with mites, aphids and other small arthropods. Eggs are deposited at night, hung on a slender stalk of silk usually on the underside of a leaf. Immediately after hatching, the larvae molt, then descend the egg stalk to feed. They are voracious predators, attacking most insects of suitable size, especially soft-bodied ones (aphids, caterpillars and other insect larvae, insect eggs). Their maxillae are hollow, allowing a digestive secretion to be injected in the prey. Lacewing larvae are commonly known as “aphid lions” or “aphid wolves”. In some countries, Lacewings are reared for sale as biological control agents of insect and mite pests in agriculture and gardens.

Ooh, here’s another time bomb for the aphids! Do you see the Syrphid egg that looks like a grain of rice on the lower left corner?

Mama Hover Fly has cleverly planted an egg among the aphid colony, so that when the larva hatches it will have plenty of aphids to eat. Many species of hover flies (family Syrphidae) have aphidophagous larvae (that feed on aphids).

A bloated, brown Oleander Aphid is found on the underside of a milkweed leaf. It is an “aphid mummy” that has been parasitized by the Aphid Mummy Wasp, Aphidius sp. (family Braconidae).

Aphid Mummy Wasps, Aphidius sp. (family Braconidae) are small wasps, typically less than 1/8 in. long. The female wasp lays a single egg in an aphid. When the egg hatches, the wasp larva feeds inside the aphid. As the larva matures the aphid is killed and becomes bloated and mummified, usually turning tan or golden in color. The adult parasitoid chews its way out of the mummy leaving a hole.

An Aphid Mummy Wasp, Aphidius sp. (family Braconidae) is injecting an egg into a tiny aphid on a terminal milkweed leaf. Why doesn’t she choose a bigger host? The wasp appears to have an injured, crumpled left wing. Perhaps she’s not capable of attacking a full-sized aphid in her compromised condition?

Here’s another Aphid Mummy Wasp, Aphidius sp. (family Braconidae) in search for host aphids on a milkweed.

Side view of the same Aphid Mummy Wasp on the edge of the milkweed leaf.

A tiny insect barely 3 mm long is resting on the underside of a milkweed leaf. Magnified under the macro lens, it turns out to be the Twenty-spotted Lady Beetle, Psyllobora vigintimaculata (family Coccinellidae) – a mouthful of a name for a critter only 2-3 mm in length. How are the spots counted, when the markings on the beetle’s elytra are irregular blotches of two different colors?

The Twenty-spotted Lady Beetle, Psyllobora vigintimaculata (family Coccinellidae) is found in North America, especially the west coast. The elytra have dark, gold or bicolored spots on a white background. There are four or five distinctive dark spots on the pronotum arranged in an “M” shape. The patterns on the elytra are highly variable. The species is found in early spring, occurring in numbers on the foliage of various shrubs. In summer and fall, they are often found on plants with powdery mildew on which the beetles feed. It has been proposed that the beetles be used as an alternative to fungicides for the control of the fungus in agricultural settings. How about that – a Lady Beetle that doesn’t eat aphids!