Pollinator Post 5/31/23 (2)

A Field Ant, Formica subpolita (family Formicidae) is foraging on the trail.

Formica is a genus of ants of the family Formicidae, commonly known as wood ants, mound Ants, thatching Ants, and field Ants. Formica ants tend to be between 4 and 8 mm long. As the name wood ant implies, many Formica species live in wooded areas where no shortage of material exists with which they can thatch their mounds (often called anthills). Some species are inhabitants of more open woodlands or treeless grasslands or scrubland. Many species maintain large populations of aphids on the secretions of which they feed and which the ants defend from other predators. They also prey on other insects. Due to their large size and diurnal activity, they are among the more commonly seen ants in northern North America.

Most Formica species are polygynous (have multiple queens per colony), and some are polygamous (have multiple nests belonging to the same colony). Queens may be singly or multiply mated, and may or may not be related. Wood ants typically secrete formic acid when alarmed. Unlike other ants, the genus Formica does not have separate castes, which are based on an individual’s specialization and morphology.

As I watch a Hoverfly feed on pollen of a California Dandelion, Agoseris grandiflora, I notice that she is also defecating as well. My first documentation of this activity!

Hmm, there’s a dark shadow deep in the floral tube of a Sticky Monkeyflower. ’Tis the season of the Small-headed Fly! I need to find out if they are here.

(Disclosure: I only engage in this destructive activity once a year.) Carefully I peel away one side of the Sticky Monkeyflower to expose the occupant inside. It is indeed a Small-headed Fly, Eulonchus sp. (family Acroceridae). The fly is so cold or fast asleep it doesn’t even budge. (Note that the reproductive structures of the flower have sprung up as they are released from their confinement. The white, two-lobed stigma is usually visible from the front of the flower, hiding the yellow stamens behind it in the floral tube. This is apparently a young flower, and the anthers have yet to release their pollen.)

Here’s a close-up of the Small-headed Fly, or North American Jewelled Spider Fly, Eulonchus sp. (family Acroceridae). Both common names are appropriate, as the fly indeed has an undersized head, and its abdomen is a gleaming blue iridescence in the sun.

My acquaintance with this fly goes back a few years when I was a volunteer at the Bridgeview Pollinator Garden in Oakland. Each year I would watch the flies appear on the Sticky Monkeyflower, Diplacus aurantiacus just as the plant begins to bloom in May. In the early morning, the flies would be safely tucked within the floral tubes, with only their shiny butts visible. As the sun begins to warm up the air, the flies would wake up, move outside the flowers to bask and groom themselves. Often their backs are covered with pollen if the stamens on the roof of their chosen overnight shelter were dispensing a golden shower while they snoozed.

Just a couple of hundred yards further, I come across this Eulonchus on the lower lip of a Sticky Monkeyflower, its back covered with pollen that has fallen on it while it was sheltering inside the floral tube.

As far as I know, this Eulonchus species has a close relationship with the Sticky Monkeyflower. The fly’s whole life revolves around the flowers. They sleep, feed, court and mate around the plant and its flowers. And since they are often covered with pollen, it’s hard not to believe that they are significant pollinators for Diplacus aurantiacus.

On the same plant, I find half a dozen more Eulonchus flies tucked singly in the flowers. Some are beginning to stir and become active. Such fun to watch these clowns! As much as I have fun with them, I am also aware of their darker side.

As far as is known, all Acroceridae are parasitoids of spiders. Not just any spiders, but the Mygalomorphs of a more ancient lineage. This Acrocerid species, most likely Eulonchus tristis is known to parasitize the California Turret Spiders. Females lay large numbers of eggs near their host nests. After hatching the young larvae, called planidia seek out the spiders. The planidia can move in a looping movement like an inchworm and can leap several millimeters into the air. When a spider contacts an Acrocerid planidium, the planidium grabs hold, crawls up the spider’s legs to its body, and forces its way through the body wall. Often, it lodges near the spider’s book lung, where it may remain for years before completing its development. Mature larvae pupate outside the host. The Acrocerid adults are nectar feeders with exceptionally long probosces which are folded on the underside of the body when not in use. Acrocerids are rare but can be locally abundant. They are believed to be efficient pollinators for some native plants, including the Sticky Monkeyflowers.

At Diablo Bend, I check on the Lupin Aphids on the infested Silverleaf Lupine, Lupinus albifrons. Yes, they are still there, in many sizes and ages, on the fresh flowers…

… as well as the dried up flowers. The plant is already wrapping up its season. What’s to become of these aphids?

Aphids, depending on species, are able to pass winter in two ways. If they are holocyclic i.e. possess an egg-laying stage, they usually overwinter as eggs. Aphid eggs are extremely cold-hardy. The other strategy is adopted by those aphids that are anholocyclic; they pass the winter as an active stage, either as an adult or immature nymph. A potential advantage of using an active overwintering stage and not an egg, is that if they survive the winter, they are able to start reproducing sooner.

Lupin Aphids, Macrosiphum albifrons is believed to survive and reproduce on lupines through the winter in the parthenogenetic viviparous stage. In simple language, as females that give live birth to clones of themselves without having to mate.

A bloated Ladybeetle larva is resting on a developing pea pod of Silverleaf Lupine.

A younger Ladybeetle larva is feeding on an aphid on a flower of Silverleaf Lupine.

A lone Indian Paintbrush, Castilleja sp. is blooming beautifully among the lupines at Diablo Bend. The showy red structures of Indian Paintbrush are technically not petals, but bracts, a type of modified leaf. The tip of the sepals are tinged with red as well.

The petals are usually green or yellow, and curiously arranged, with the upper two extending out into a long, pointed beak that envelops the stamens and style. With tubular design and red color, the flower is especially adapted for pollination by hummingbirds. The hummers have long slender bills that allow them to reach the nectar rewards at the base of the flowers.

The knobby structure hanging out of the floral tube is an immature bilobed stigma. The stamens are located just behind the entrance of the floral tube.

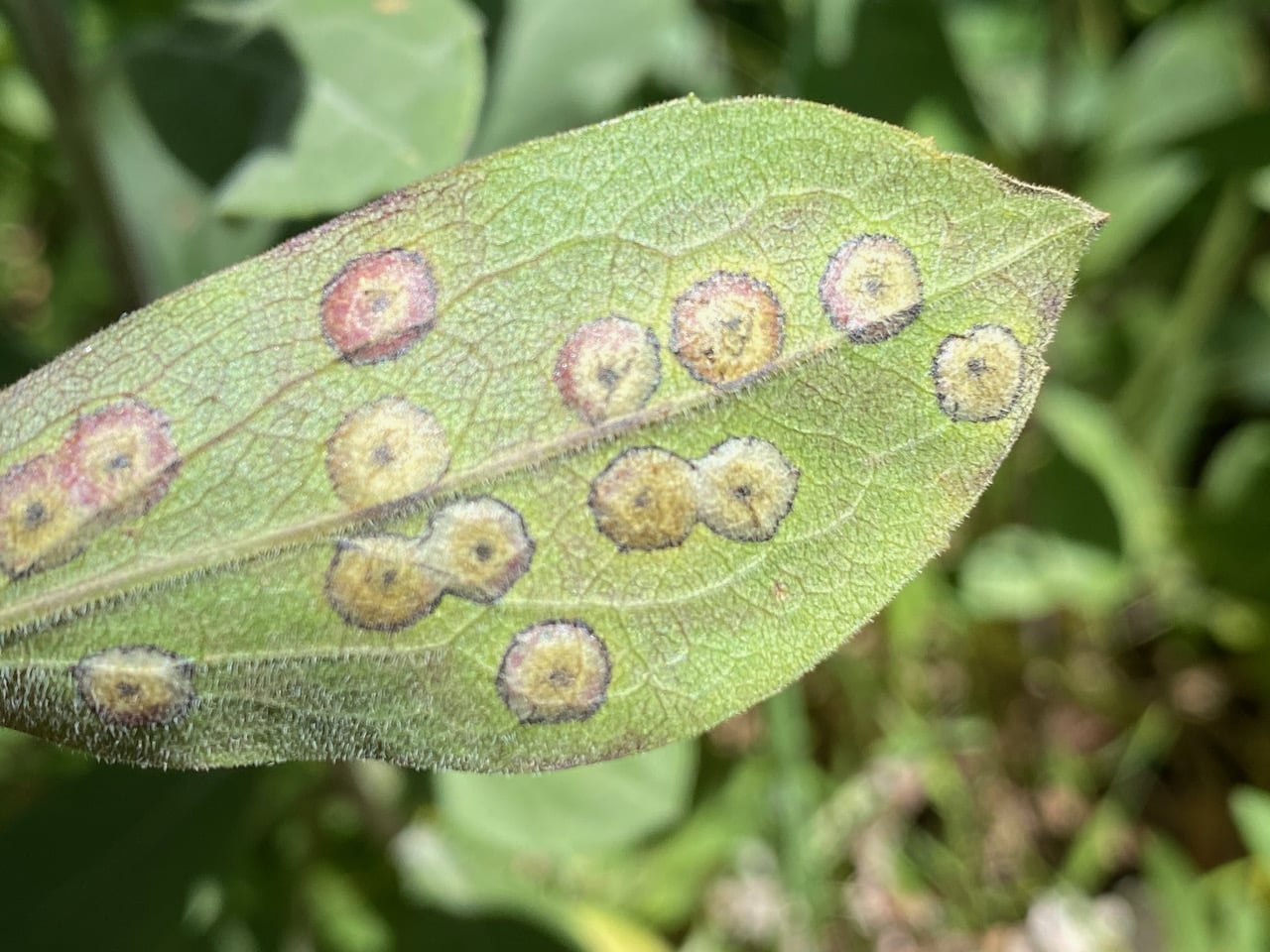

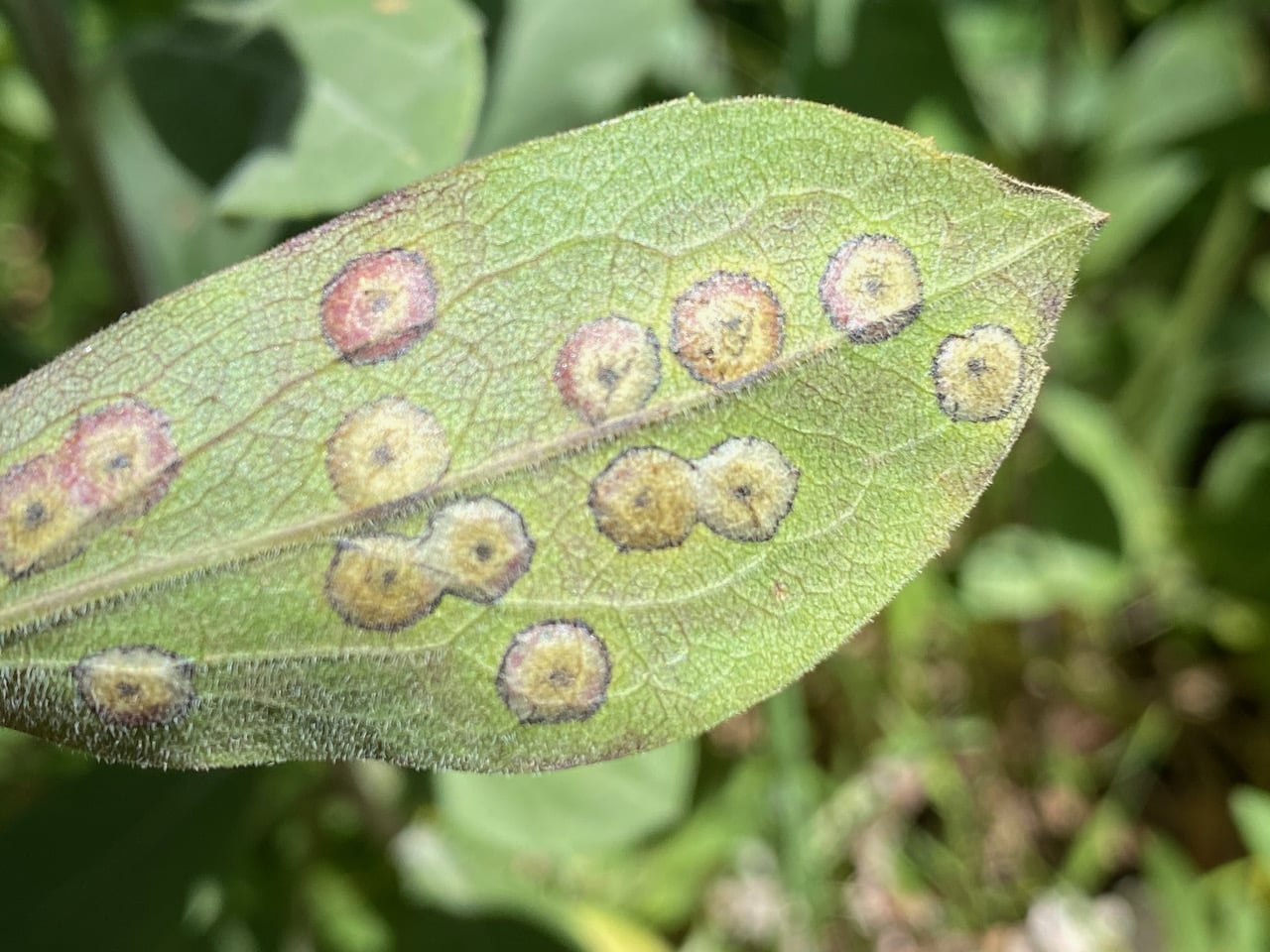

Seen commonly last year on the California Goldenrod, Solidago velutina along the shady section of Skyline Trail, these bizarre leaf galls have made their appearance again!

It’s a well-known goldenrod gall, induced by the gall midge Asteromyia carbonifera (family Cecidomyiidae). The midge induces flat, circular galls in the leaves of various goldenrods (Solidago). One to ten or more larvae develop in each gall. Color and size of the gall vary by host species and number of larvae. The galls contain a symbiotic fungus, Botryosphaeria dothidea, which the larva apparently does not eat. The fungus seems to confer some protection against parasitoid wasps. Females carry spores of the fungus.

The blister galls are also visible on the underside of the leaf.

The scat was a wet pile earlier this morning when I passed it. Now at 1:30 pm, it has somewhat dried up and a swarm of Secondary Screwworm Flies have gathered on it. Apparently animal carrion is not the only thing that attracts them. A carnivore’s scat may exude the same attractant to these blow flies.

The Secondary Screwworm, Cochliomyia macellaria (family Calliphoridae, commonly known as blow flies) ranges throughout the United States and the American tropics. The body is metallic greenish-blue and characterized by three black longitudinal stripes on the dorsal thorax. Females are attracted to carrion where they lay their eggs. These screwworms are referred to as “secondary” because they typically infest wounds after invasion by primary myiasis-causing flies. While the flies carry various types of Salmonella and viruses, C. macellaria can also serve as important decomposers in the ecosystem. In a lifetime, a female may lay up to 1000 or more eggs. Females may also lay their eggs with other females, leading to an accumulation of thousands of eggs. The larval stage of C. macellaria is referred to by the common name of secondary screwworms; this is due to the presence of small spines on each body segment that resemble parts of a screw. The larvae feed on the decaying flesh of the animal that they have been laid on until they reach maturity. Eventually the larvae fall off the food source to pupate in the top layer of the soil. Adult females will continue to feed on tissues of animals; however, now they preferentially feed off of live tissues and tissue plasma. Adult males will no longer consume tissue, but instead will eat nearby vegetation and take nourishment from floral nectar.