Pollinator Post 2/27/25 (2)

A Greater Bee Fly, Bombylius major (family Bombyliidae) is hovering under a cluster of Manzanita flowers, its wings a blur.

Bombylius major, commonly known as the Greater Bee Fly is a parasitic bee mimic fly in the family Bombyliidae. It derives its name from its close resemblance to bumble bees. Its flight is quite distinctive – hovering in place to feed, and darting between locations. The species has long skinny legs and a long rigid proboscis held in front of the head. Bombylius major is easily distinguished from the other local species of Bombylius for having wings with dark leading edge, hyaline trailing edge with sharp dividing border. This feature is visible even as the fly is hovering. Adults visit flowers for nectar (and sometimes pollen) from a wide variety of plant families, excelling at small tubular flowers, and are considered good generalist pollinators. Often the pollen is transferred between flowers on the fly’s proboscis.

The bee fly larvae, however, have a sinister side. They are parasitoids of ground-nesting bees and wasps, including the brood of digger bees in the family Andrenidae. Egg deposition takes place by the female hovering above the entrance of a host nest, and throwing down her eggs using a flicking movement. The larvae then make their way into the host nest or attach themselves to the bees to be carried into the nest. There the fly larvae feed on the food provisions, as well as the young solitary bees.

Its skinny long legs lightly resting on the opening of the flower, the Bee Fly constantly flaps its wings while probing a manzanita flower for nectar with its long proboscis.

I approach the Bee Fly as close as I can and turn on the video to record its behavior.

There seems to be more Digger Bees (Anthophora sp.) than the bumble bees on the manzanita flowers today. These hyperactive bees zip around the bushes, buzzing loudly.

This male has landed on a cluster of flowers to take nectar. It is fairly easy to tell the sexs apart in this species as the males have a yellow clypeus on their face. Foraging females are often seen with yellow pollen in the scopae on their hind legs.

Male.

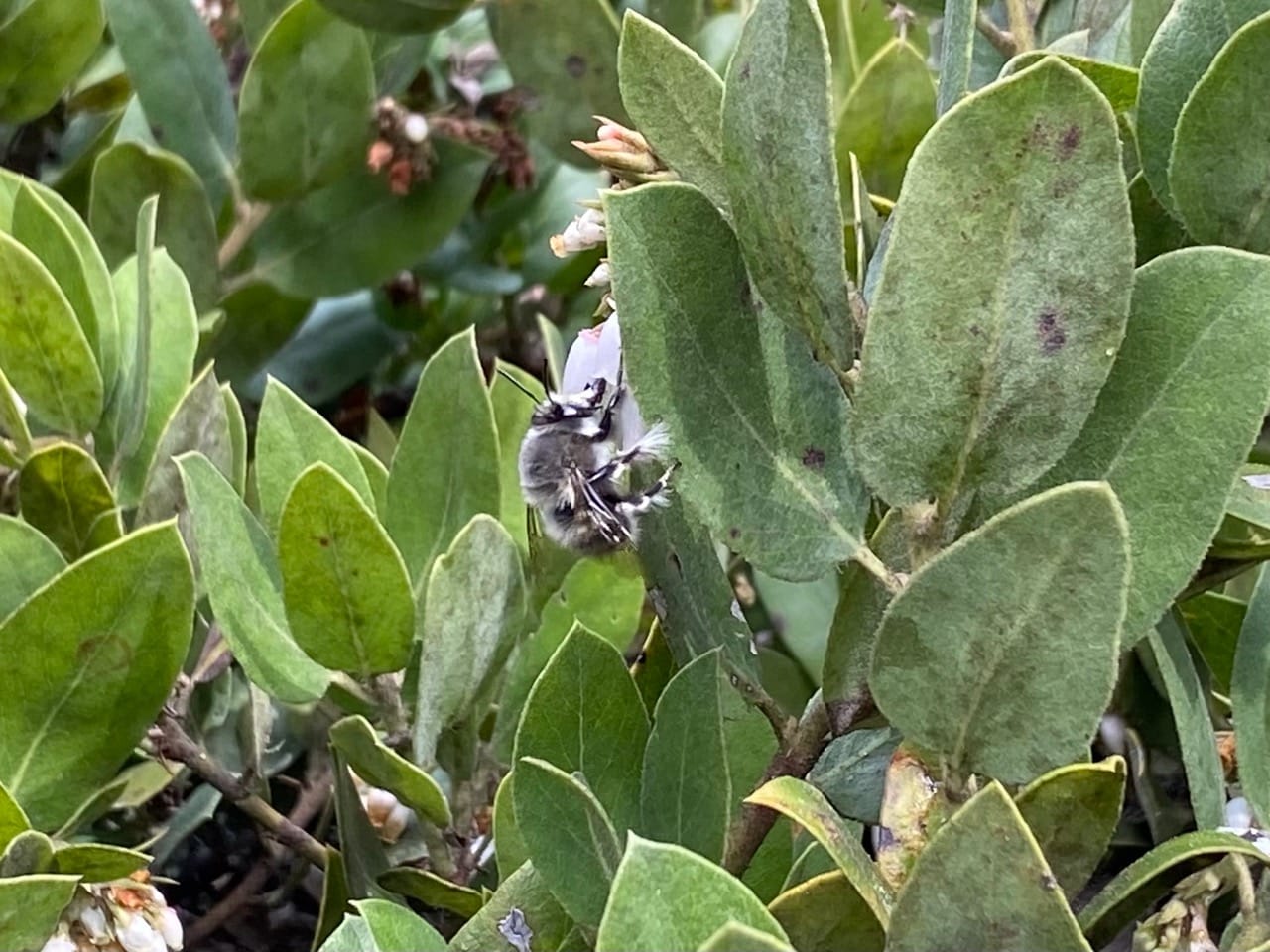

A male Pacific Digger Bee, Anthophora pacifica (family Apidae) is taking nectar from a manzanita flower. Note the tufts of long white hairs on his legs. Females do not have these, but instead they have scopae on their hind legs.

Ooh, that looks like a female Digger Bee. Note the shaggy hairs on her hind leg that make up the scopa for collecting pollen.

Another female Anthophora backing off from a manzanita flower.

This female Pacific Digger Bee, Anthophora pacifica (family Apidae) has collected some yellow pollen in her scopae. Like the bumble bees, female Anthophora are capable of buzz pollination. Hanging upside-down on the drooping flower, the bee disengages her wings from her flight muscles, then vibrate these muscles at a high frequency. Her vibrating body shakes the pollen from the poricidal anthers of the manzanita flower. The bee gathers the pollen that lands on her belly, and packs it into her scopae for her trip back to the hive.

The Giant Trillium has been labeled Wake Robin, white-flowered form of Trillium chloropetalum from San Bruno Mountain. The white petals provide a clear contrast to the maroon-colored anthers. The small black insect near the anthers gets my attention way before I realize that it is in the fangs of a pale Crab Spider (family Thomisidae) on a sepal. Do you see the spider?

Members of the family Thomisidae do not spin webs, and are ambush predators. The two front legs are usually long and more robust than the rest of the legs. Their common name derives from their ability to move sideways or backwards like crabs. Most Crab Spiders sit on or beside flowers, where they grab visiting insects. Some species are able to change color over a period of some days, to match the flower on which they are sitting.

As I approach for a closer shot, the spider scurries away to hide under a leaf, dropping its prey along the way. The prey appears to be a wasp with very long antennae. An Ichneumonid wasp? Was it here in search of hosts and/or nectar?

The Ichneumonidae, also known as the Ichneumon Wasps, or Ichneumonids, are a family of parasitoid wasps. They are one of the most diverse groups within the Hymenoptera (the order that includes the ants, wasps and bees) with about 25,000 species and counting. Ichneumon Wasps attack the immature stages of insects and spiders, eventually killing their hosts. They play an important role in the ecosystem as regulators of insect populations.

The Ichneumon wasps have longer antennae than typical wasps, with 16 segments or more as opposed to 13 or fewer. Ichneumonid females have an unmodified ovipositor for laying eggs. They generally inject eggs either directly into their host’s body or onto its surface, and the process may require penetration of wood. After hatching, the Ichneumonid larva consumes its still living host. The most common hosts are larvae or pupae of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths), Coleoptera (beetles) and Hymenoptera. Adult Ichneumonids feed on plant sap and nectar. Females spend much of their active time searching for hosts while the males are constantly on the look out for females. Many Ichneumonids are associated with specific prey, and Ichneumonids are considered effective biological controls of some pest species.

Here’s another Giant Trillium flower in the same bed. The anthers are much paler, with a mere blush of pink. Yellow pollen is produced in two rows along the edges of each anther. It is not often one gets to see the pistil of the trillium flower without having to pry open the flower. This wide open flower offers a clear view inside – the stigma appears to be a large, irregular, wrinkled structure in the center. Who pollinates these flowers? The fact that a Crab Spider is hunting in these flowers is a hopeful sign that insects are visiting them.

The Hound’s Tongue, Adelinia grandis is blooming beautifully in various shady spots in the garden. I watch as a Digger Bee, Anthorphora sp. sips nectar from these flowers, but am not quick enough to snap its picture.

Why do the pink buds of the Hound’s Tongue open up into blue flowers?

And why do Hound’s Tongue flowers turn pink again when they fade?

Clusters of flowers are borne on long stalks, pink in bud changing to blue. There are five fused petals with white appendages forming a central crown around the reproductive parts. The flowers change color, perhaps guiding pollinators whether a specific flower is worth visiting for pollen and nectar. Color signaling occurs in the flowers of more than 70 plant families to direct pollinators. Examples include Forget-me-nots, and Heliotrope, also in the Borage family. Bees see blue colors well, but not reds. Hound’s Tongue flowers contain anthocyanin, a pigment that changes color with pH. Immature pink flowers may signal to bees, “Not ready; move on.”, the mature blue flowers, “Ready for pollination.”; and the fading blue-purple of the aging flowers, “I’m done; don’t bother.” What’s more, bees perceive ultraviolet colors of the nectar appendages, which appear white to us. There’s so much more than meets our eyes!

Walking past the white Giant Trillium again, I look for the Crab Spider that I have scared off earlier. There it is, feeding on the wasp on the same leaf where it has dropped the prey.

The spider is so pale one can barely make out its outline. I won’t bother you this time, little spider – bon appetit!

Ooh, there’s a largish insect perched upside-down on a manzanita flower! It has long, sturdy legs and an elongate abdomen with a pointed tip. Note the white lollipop-like structure that sticks out from the fly’s thorax under the folded wings? It is one of a pair of halteres. And it tells me that I am looking at a fly.

Halteres are small ‘drum stick or lollipop” shaped structures found under a fly’s wings. They are modified hind wings and are used for balance when in flight. They are sophisticated gyroscopes that oscillate during flight. This is why flies are called Diptera (two-winged) – unlike other insects, they have only a single pair of wings, the other pair having been modified into halteres.

Another view of the fly from the underside as it probes another flower for nectar. Note the pair of halteres.

As the fly lifts ifs head from the flower, I realize that it is a Dance Fly (family Empididae) with a long proboscis.

Dance Flies, in the family Empididae, get their name from the habit of males of some species to gather in large groups and dance up and down in the air in the hopes of attracting females. They are predominantly predatory and they are often found hunting for small insects on and under vegetation in shady areas. Both genders may also drink nectar. Male dance flies give their sweeties a nuptial gift to eat while they mate. The gift is thought to enable her to complete the development of her eggs. Males may wrap their gifts in balloons of silk or spit, hence the other common name of Balloon Flies.

On the way out the side gate, I pass the plant sale station. Among many plants on offer are gallon pots of Catalina Nightshade, Solanum wallacei already in bloom.

Compared to other nightshades, this species has large, slightly ruffled petals. See the dark bruises on the yellow anther cone in the middle of the flower? I call these “bee hickeys” – the flower has been embraced by a buzz pollinating bee.

Solanum flowers are often used as the standard model for the study of buzz pollination. The tubular anthers are clustered in the center of the open-faced flower, forming an anther cone surrounding a sturdy style, These anthers are poricidal, meaning they have a tiny opening or pore at their tip through which pollen is expelled. When the flower is shaken or vibrated at the appropriate frequency, the dry pollen is released through the pores, similar to the way salt shakers work. Solanum flowers tend to nod or droop, so pollen release is aided by gravity as well.

How does buzz pollination work? When a bumble bee attempts to collect pollen from a Solanum flower, it grasps the anther cone with its legs or mouthparts. Hanging upside down, the bee decouples its wings from its flight muscles in its thorax, so that when it vibrates those flight muscles, the wings don’t move, but its body vibrates violently. The bee’s buzz suddenly shifts from the low hum typical of flight to a fevered high pitch that is audible to a human ear. The vibration shakes the pollen out of the anthers onto the bee’s body. Very efficiently, the bee grooms the pollen into its pollen baskets for transporting to the hive. On subsequent visits to other flowers of the same species, the pollen that remains on its body might rub off on the protruding stigma, effectively pollinating the flower. Honey bees are not capable of buzz pollination. The technique is used mainly by bumble bees, carpenter bees, some digger bees, and sweat bees.

Approximately 6-8% of flowering plants are dependent on buzz pollination, many from unrelated families, representing examples of convergent evolution. The traits shared by these flowers include: pendant flowers, radial symmetry, reflexed petals, prominent cone of stamens with short robust filaments and poricidal anthers, a simple style that protrudes from the tip of the anther cone, and an absence of nectar. A prominent example of a buzz-pollinated flower in our native flora is the shooting star (Primula) in the primrose family.